TechNode Global’s series on the Philippines delves into why Filipino startups are attracting venture capital (VC) money in droves. In this third part, we explore how much Covid-accelerated digitization boosted the country’s ‘Iron Triangle’ – e-commerce, logistics, and fintech – startups, and how the startup Davids are battling the Goliath super apps to carve out their own niches. Catch up with Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

The Iron Triangle was a phrase coined by Jack Ma of Alibaba following the tech giant’s eventual dominance of three interlinked sectors – e-commerce (Alibaba and Tabao), logistics (Cainiao), and fintech (Alipay) – following the launch of Alibaba during the 2003 SARS epidemic in China.

Almost 20 years later, the parallels are almost uncanny in the Philippines. COVID-19 accelerated digitalization was an even bigger boon for the country’s Iron Triangle startups compared to their Southeast Asian peers. Google’s e-Conomy SEA 2021 report found that the Philippines had the highest proportion of new users who began consuming online during the pandemic at 20 percent.

The Philippines has seen 12 million new digital consumers since the start of the pandemic (up to the first half of 2021), of which 63 percent are from non-metro areas and 99 percent say that they intend to continue using these services going forward. Google believes that despite rapid growth, there remains significant headroom since the Philippines has the lowest digital consumer penetration in the region, with only 68 percent of internet users consuming online services.

Southeast Asia is dominated by super apps that fulfill all three functions in the Iron Triangle, such as Gojek, Grab, Sea (Shopee), or Alibaba (Lazada). But since there is a much bigger pie in the Philippines, local startups can effectively carve out niches in specific verticals while catering to local mores.

TechNode Global spoke to several startups doing exactly that in all three sectors of the Iron Triangle.

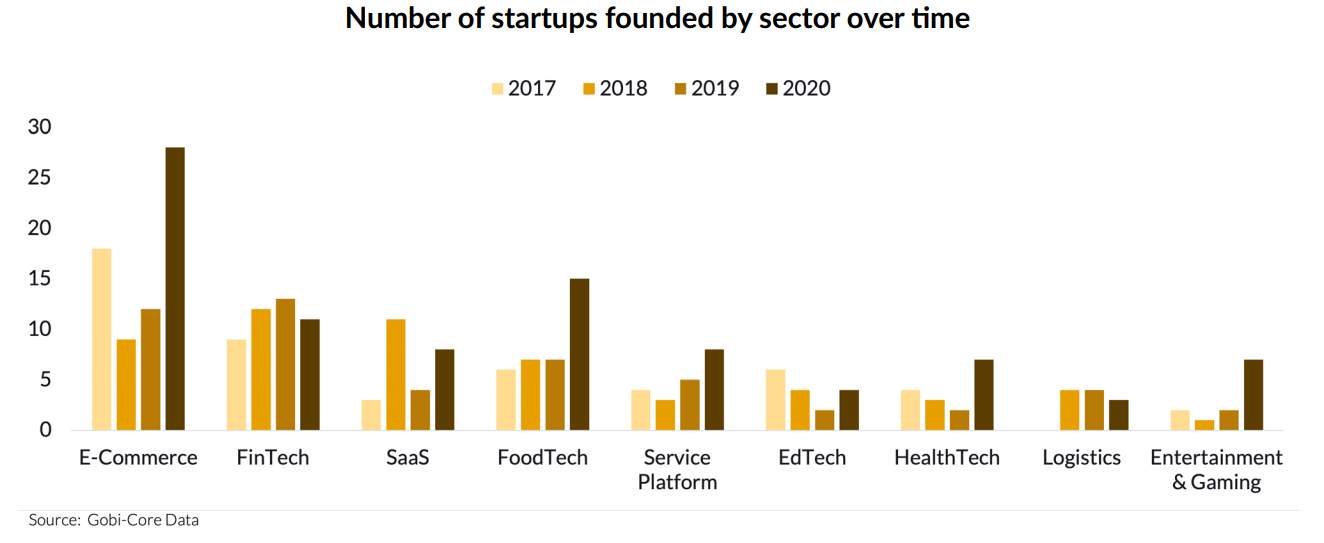

E-commerce leads the pack

The Philippines was the fastest growing market in Southeast Asia, driven by strict lockdowns as well as a tipping point on the adoption of certain digital services. Its 2021 gross merchandise value (GMV) is estimated at $17 billion in 2021, a whopping 93 percent surge year-on-year. But there’s much much more room to grow: By 2025, Google expects the Philippines’ overall internet economy to reach $40 billion, at a 24 percent compound annual growth rate.

The steep 93 percent growth rate is backed by an even larger 132% growth in the Philippine e-commerce sector to $12 billion in 2021, up from $5 billion in 2020.

The big boys in the local e-commerce space are largely foreign-owned, backed by the country’s massive conglomerates, or more likely, both. According to the Gobi-Core Philippine Startup Ecosystem Report 2021, the Top 4 e-commerce marketplaces by monthly visits are Shopee (owned by Singapore’s Sea), Lazada (owned by Alibaba), Zalora (half-owned by Ayala Corp, one of the Philippines’ oldest and largest family conglomerates) and eBay from the U.S.

So how did the Philippine upstarts separate themselves from the busy e-commerce pack? Saul Molla, founder and CEO of online gifting company FlowerStore, recounted: “By 2018, horizontal players like Lazada and Shopee were totally established in the Philippines. We knew that around 10 percent of online purchases were bought to be given as a gift to another person, be it a holiday or special occasion.”

“E-commerce has been greatly benefiting from the pandemic as many people tried ordering online for the first time. What otherwise would have taken probably 10 years, we got it accelerated. Gifting as an e-commerce vertical was not different: we are in the business of allowing people to connect through gifts, and when they couldn’t connect physically, this became even more important,” he added.

“We are in the business of allowing people to connect through gifts, and when they couldn’t connect physically, this became even more important.” – Saul Molla

Molla – formerly the CFO at Lazada Philippines – said horizontal players didn’t have a customer experience for gifting: “If you try to search in Shopee or Lazada for a product for example for a birthday, I bet you will get thousands of results but most of them will be totally crap.

“Moreover, you cannot select the exact date you need the product to arrive or add a message with your order. This is where our opportunity was born: to provide a curated affordable assortment for every occasion with a best-in-class gifting customer experience and express delivery,” he said.

FlowerStore’s proposition has appealed to VCs: Following a $1.5 million seed round in 2019, FlowerStore closed a pre-Series A round in November 2021.

Another niche vertical in e-commerce is cloud kitchens. Launched in 2019 prior to the pandemic, CloudEats banked on Filipinos being highly ‘cuisine-curious’ and spending around 30 percent of their income on food.

CloudEats co-founder and CEO Kimberly Yao said, “Food is a big part of Filipinos’ everyday and family life. The population is also quite young and very tech-savvy so we believed that food delivery and the rise of online-only brands would experience unprecedented growth even prior to the pandemic.”

Her co-founder Iacopo Rovere – formerly CEO of foodpanda Philippines – believes cloud kitchens are here to stay, even post-pandemic. “COVID-19 increased the growth pace at which online food delivery was embraced by Filipinos. Our expectation is that the user behavior and reliance on food aggregators will keep on growing and last over time, even after the pandemic,” he remarked.

CloudEats has also tapped VCs recently, raising $5 million in a significantly oversubscribed Series A in October 2021. Rovere recounted, “At the beginning of our venture, investors were very split among the different models of cloud kitchen (real-estate, kitchen as a service or KaaS, virtual brands). Everyone had very diverse opinions on what the future of online food would look like.

“Fast forward two years and most of the investors we speak to are now inclined towards KaaS and virtual brands, shifting slightly away from the more capital-intensive real-estate model,” he pointed out.

Yao said the growing interest in cloud kitchens is predicated on the belief that the pandemic is an ongoing concern and a situation that we need to live with in the long term.

“Our business model is heavily supported by the changing user behavior that was put into hyper-drive by Covid-19. The result is higher confidence by investors in the cloud kitchen model beyond simply riding a trend,” she said.

Friendly fintech regulators

For many years, the local fintech scene has been dominated by two digital wallets, both backed by the local telcos. In the blue corner is GCash with 46 million users and backed by Ayala Corp’s Globe Telecom and Ant Group (Alibaba’s parent company), among others. In the red corner is PayMaya with 40 million users, and the backing of PLDT (Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company), Chinese superapp Tencent and global private equity giant KKR.

The nature of fintech funding calls for massive resources, in addition to navigating regulation for uncharted waters. For the non e-wallet and smaller players, carving a niche means finding their own ways to bring financial inclusion to an estimated 51 million unbanked Filipino adults.

Luckily, regulators have been more than helpful in this space. Per the Gobi-Core Philippine Startup Ecosystem Report 2021, the rollout of the Philippine National ID System requires registrants to have bank accounts, and accounted for 5.3 million Filipinos opening bank accounts as of September 2021. The Philippine government’s move to disburse pandemic-related cash resulted in 4.5 million new e-money accounts.

Gobi-Core expects fintech startups to see continued policymaking and regulatory support as the PhilSys IDs are rolled out across second-tier cities and rural regions, given the Philippine Central Bank (BSP)’s public target to see 70 percent of the population banked by 2023.

To Greg Krasnov, the Philippines represents a $140 billion retail savings market and a $100 billion unsecured consumer lending opportunity. The founder and CEO of digital bank Tonik told TechNode Global, “Over 90 percent of the population has never been lent to by a bank because they’re not lending to anybody without credit history or bank account. That makes the Philippines one of the least penetrated markets in terms of consumer lending anywhere in Southeast Asia.

“It’s 3-4x lower on a per capita or per GDP basis than Indonesia or Vietnam – countries that are at a similar level of GDP per capita as the Philippines. That represents a very large opportunity, going into the tens of billions of dollars for consumer lending, that is untapped.

“At the same time, it’s a very large deposit market. There are $300 billion of deposits in the system already, but only 10 percent of those deposits are lent out as loans to consumers. That’s an acute misallocation. I think it’s unfair to Filipinos that the banks take their money as deposits, but only lend it to their corporate clients. We’ll have to change that and create a more equitable balance for the Philippine banking system,” he enthused.

When Krasnov approached BSP for a bank license in 2018, they found an unusual level of openness to experimentation, a rarity among financial authorities.

“BSP suggested Tonik go for a rural bank license, but we would be BSP’s sandbox partner so that we could learn together how to create a digital bank. We were okay being the guinea pig and worked with BSP to get Tonik off the ground. They used that experience to create the regulations, which they announced in November 2020,” Krasnov recounted.

He added, “The regulatory climate in the Philippines in this regard is very different from most of the places in the region or for that matter, the world. The regulator is adopting more of a kind of startup ecosystem mentality: ‘Let’s get something to market, then let’s iterate to find the right market fit.

“This is diametrically opposite to Singapore’s approach which is ‘Let’s create a couple of volumes of restrictive and prescriptive regulations about what a digital bank should look like. Now let’s hope somebody comes in and takes it. I believe the Philippines is a big differentiator because of the way the regulator approaches things,” Krasnov said.

Less than a year after its March 2021 launch, Tonik is one of the fastest-growing neobanks globally, reaching $100 million of consumer deposits within its eighth month of operations, while pulling in a $131 million Series B led by Japan’s Mizuho Bank.

This unique regulatory environment has snagged the attention of both VCs and foreign fintechs, as Philippine fintechs have been raising record rounds or being snapped up by larger fintechs with expansion in mind.

Making logistics work for SMEs

For logistics tech startups in the Philippines, the story is very similar to e-commerce in terms of market leadership, while it mirrors the fintech space in dealmaking. The top dogs are either Southeast Asian unicorns or spin-offs of local logistics players and family conglomerates.

The dominance of big players is partly due to the high logistics costs of doing business, which itself is linked to the country’s archipelagic makeup.

The OECD estimated the market size of the logistics transport services sector at $11 billion in 2019, accounting for 4 percent of the Philippine GDP. Road transport accounted for 40 percent of freight transport revenue, while maritime transport came in at 35 percent. The cost of logistics to sales is 27 percent – higher than Indonesia (21 percent), Vietnam (16 percent), and Thailand (11 percent).

The industry also includes freight forwarding and warehouses, where 75 percent of operators are micro- and small enterprises, and small package delivery services, where demand is being driven by booming e-commerce.

This space is where logistics tech enablers like Airship – ranked in the Top 3 at the Philippine leg of the She Loves Tech 2021 competition – are hoping to carve out their niches.

Co-founder and CEO Rachelle Uy said, “Even before building Airship, as early as 2011, we saw the demand and the rise of startup couriers because it’s a business that’s easy to understand and easy to set up, but very hard to sustain because of the technology and expertise needed once it grows and scales up. So we are there to help these startup couriers thrive.

“Before Airship, we were running a dev shop, and our clients often came to us with the same problems, exposing us to best practices as well as challenges of logistics companies. This helped us discover the need for building Airship, an end-to-end system with an easy onboarding process, which has never been done before in the case of the Philippine logistics market.

“As e-commerce sellers ourselves, we were very familiar with the receiving end or client of couriers. We were able to compare various user experiences from different major couriers as end-users and incorporated the best features into an efficient system, building Airship as a full suite,” she told TechNode Global via email.

Logistics players have also been unwitting beneficiaries of Covid-19 accelerated digitization, which led to increased trust and willingness to pay for quality digital services in the Philippines.

When Airship was founded in 2018, Uy and her co-founder Charlotte Yu found that people were unwilling to pay shipping fees above $1 (Php 50). Those that did often didn’t trust the sellers and thus preferred to pay via Cash on Delivery.

“When the pandemic struck, logistics became a necessity instead of a luxury. People were willing to pay even beyond $2 (Php 100) for shipping. There was a rise in on-demand logistics (point-to-point deliveries) because it has the least contact points, so a lot of startup on-demand couriers popped up at the height of the pandemic. On top of that, most people had lost their jobs and thus became couriers.

“We were able to stabilize our product by late 2020, so Airship came at the right time to support the adoption of consumers to digital services and e-commerce. Contactless deliveries, both on-demand and next-day delivery services were driven by strict lockdowns,” Uy said.

“Eventually, as logistics and e-commerce businesses started to scale, they needed a solution to support the increasing package volume. That’s when Airship came into the picture – we helped them transition to automated processes to improve efficiencies, while keeping up with rising standards in the e-commerce industry,” she added.

Dealmaking in the logistics space evolves around smaller players like Airship that build their own niches. In May 2021, zennya raised $1.2 million to expand its virtual hospital ecosystem which includes a delivery network of doctors, nurses, therapists, motorcycle drivers, cars, and ambulances. Two months later, Locad raised $4.9 million to deliver an end-to-end solution for cross-border e-commerce companies.

Meanwhile, foreign players have been scooping up local niche logistics players or expanding into the Philippines, given the market’s massive room for further growth. Just last week on February 15, the Vietnamese loyalty platform Society Pass acquired Pushkart.ph, a Philippine online grocery delivery service. In November 2021, Thai logistics unicorn Flash Express launched its full service in the Philippines.

In Part 4 of this series, TechNode Global will recap recent government initiatives to spur the Philippine startup ecosystem, and get Philippine founders’ regulatory wishlists.f