Architect Tan Szue Hann, Chairman, Sustainability, Singapore Institute of Architects was a mentor at Startup Weekend Singapore 2021: Seeds of Tomorrow. The event was joined by innovators from over 21 cities from around the globe to drive awareness and innovation in sustainability. Startup Weekend resulted in around 30 ideas, with a common goal of tackling challenges arising from the climate crisis.

Szue Hann’s work involves sustainable development, green building, and curatorship of sustainable and circular design. His portfolio includes the award-winning ParkRoyal on Pickering, the SPACE Asia Hub and the O&M HQ with WOHA; the BCA SkyLab, a state-of-the-art rotatable test bed for building technologies, which won a Minister’s Award on National Day, 2017; an IT campus in Bangalore; and a smart city master plan in Bangkok, while he was heading Sustainability at Surbana Jurong.

Below are highlights of TechNode Global‘s Q&A with Tan Szue Hann, where he discussed how humanity’s ability to solve the challenges of food, energy, and waste will predicate the future of the world.

What are the trends driving the need for more sustainable business practices?

The realization that our accelerated industrialization–brought about by our endless need for consumption, volume, and efficiency–has contributed to climate change, and has put more strain on our natural environment. The fact that if we don’t stop these unsustainable practices, we are leaving behind a planet that is untenable and perhaps even uninhabitable for our future generations.

That is the altruistic way of looking at things. Businesses could also be adopting sustainable practices because of new environmental policies, incentives (or disincentives otherwise), and statutory requirements.

What are three key challenges that innovators need to overcome in addressing regional and global sustainability concerns?

The future of the world is predicated on humanity solving three problems – food, energy, and waste.

Food, its insufficiency, and an imbalance in global distribution–brought to bear by COVID-19 and its disruption on global supply chains. Climate change causes changing harvest patterns that threaten the predictability of supply, while over-cultivation leads to the desertification of land. Food self-sufficiency, and farming in urban areas, could revolutionize our traditional modes of procuring food.

Energy, or rather, an over-reliance on fossil fuels, and the downstream issues in emissions and pollution in the conversion of these fuels into electricity. Will we see a day where the world runs on clean and renewable energy?

Waste, or its ill management. Overconsumption leads to the inundation of waste in landfills, which could then pollute groundwater or have waste trickle into the ocean. Is there a way to effectively recycle most of our waste, or simply reduce it altogether?

Are there any sustainability challenges unique to Southeast Asia? Can these be addressed through global solutions, or will we need localized efforts?

Much of Southeast Asia has an abundance of arable land and intrinsic farming economies that have lasted centuries. As Southeast Asian countries begin to urbanize, swathes of arable land are being cleared in pursuit of new urban environments being built. This, coupled with rapid over-cultivation and accelerated shifting cultivation habits that do not allow for sufficient land recovery, puts a strain on natural ecosystems.

Localized efforts would certainly help, specifically in creating awareness, but global controls and environmental ratings could set the stage for change. Adjusting economic policies and market patterns to encourage more sustainable behaviors would also take time, but would likely be more global in nature.

What part is your organization doing to contribute toward sustainability?

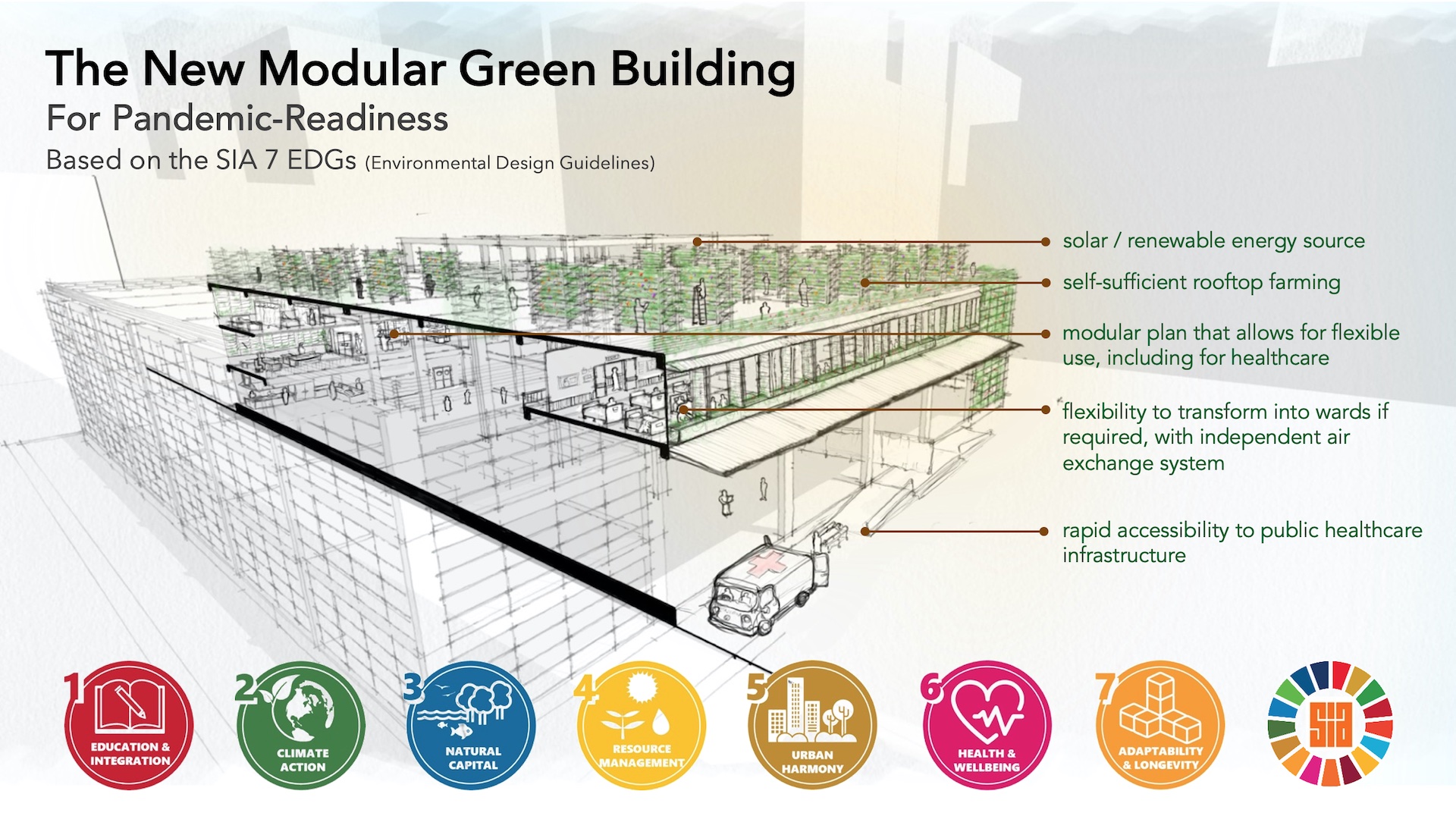

The built environment accounts for about 40 percent of the world’s energy consumption. At the Singapore Institute of Architects, our role is to encourage and ensure that the built environment industry adopts the greatest extent of sustainable practices possible. We have devised seven EDGs (Environmental Design Guidelines), themselves adapted from the UN SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), encapsulated in the SIA Green Book–a guide on how architects can lead the sustainability discussion–from minimizing our carbon footprint in the construction process to designing for longevity and adaptability for our future generations.

How do you define impact, from the perspective of sustainability?

On environmental sustainability, “impact” could be the extent to which we reduce the damage to the environment. There are metrics around how this can be measured–a reduction of GWP (global warming potential), carbon footprint, etc. However, many of the benefits of sustainable practices would be intangible–healthier cities, happier people, constant and cyclical food production, and sustained ideas, culture, and intellect.

Do you think that sustainability issues should necessarily be addressed by drastic or disruptive changes, or can we do incremental solutions that will contribute to an overall improvement?

Realistically, it would probably be a combination of both drastic changes and incremental changes–depending on the nature of the issue at hand. On energy production, for instance, a drastic change could be a blanket ban on coal mining to reduce pollutive emissions, whereas an incremental solution would be to incentivize the adoption of renewable energy (e.g. solar power) for homes. Existing behaviors, sociopolitical systems, and local economies are also crucial factors in determining if drastic or incremental changes are to be adopted; it may be more effective to employ incremental changes first, before implementing drastic solutions.

Some technological advancements have had a negative impact on sustainability, e.g., power consumption by certain blockchain technologies. How can we balance out the negative effects of increased consumption with the benefits of innovation?

I think understanding the levers of climate change and environmental degradation is important–and to what extent we can push these levers. It’s akin to simple investment–if your rewards (environmental or otherwise) exceed your original cost outlay, or if your return of investment (ROI) can be justified, then the endeavor probably may be worth pursuing.

So, in your example, if the power consumption of blockchain technologies still falls below its intended gains (efficient systems, reduction in embodied carbon, downstream energy savings) within a reasonable time frame (ROI), then it may be worthwhile. And these rewards may not be immediate or may lead to other environmental issues downstream, but we would need to evaluate the technology holistically–in relation to the entire ecosystem that it finds itself in. And in some instances, the pursuit of a technological advancement goes through years and years of investment (cost, energy, time) before the rewards become apparent.

Featured image credits: Unsplash