Editor’s note: This contributed article was written by Sheji Ho, Co-Founder of HonestDocs. It was originally published on the Plug and Play APAC blog.

By now you know COVID-19 has changed business as usual. SaaS and eCommerce stocks have hit record highs due to the pandemic, headlines continue to report a ‘New Normal’, and things will never be the same again, etc.

Needless to say, digital startup performance has accelerated and there’s a new spotlight aimed particularly at digital health:

- Teladoc, Ali Health, and Ping An Good Doctor China stocks have recently traded at all-time highs.

- JD is taking this opportunity to spin-off and take its healthcare unit public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

- GoodRx had its IPO in October 2020 at a $20 billion market capitalization.

- And Hims, a direct-to-consumer Silicon Valley-based telemedicine company selling erectile dysfunction and hair loss treatments online, is planning to go public via a SPAC.

Looking at the increased media coverage surrounding telehealth and an all-time high in Google searches for ‘telehealth’ in 2020 demonstrates how health at a social distance and on-demand is on everyone’s mind. How are companies taking advantage of this new opportunity?

Trickle-Down Digital Health in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia has seen a fair share of hype with telehealth startups popping up left and right. Even hospitals, faced with lockdowns, border closures, and a drop in domestic and international patients, are jumping onto the telehealth bandwagon using tools like Zoom, LINE, and even Facebook Messenger.

While everyone’s chasing this new shiny object, few have bothered to ask whether telehealth is even the right model for Southeast Asia.

A Tale of Two Models

With Southeast Asia as diverse as it is, it wouldn’t be fair to apply broad strokes across the entire region. Looking at SEA from a digital health perspective, we can group countries into two buckets:

1. “Mature” markets, defined by high private health insurance penetration and a sizable number of family physicians to offer General Practitioner (GP) services as a result of US/UK influence. Statistically, this resembles a normal distribution with the “fat head” covered by the major hospitals and the “long tail” offered through thousands of family physician practices. These countries would be:

- Singapore

- Malaysia

- Philippines

2. “Emerging” markets, defined by a high percentage of out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure and conversely, a low degree of private health insurance penetration e.g. 45 percent out-of-pocket spending in Vietnam and up to 76 percent in Myanmar. Patients are primarily treated at major hospitals concentrated in urban areas and statistically, this looks like a “short tail” (and in some cases “no tail”) distribution with most of the work done by major hospitals, including primary care. These countries would be:

- Thailand

- Indonesia

- Vietnam

- Myanmar

**I’ve excluded the remaining ASEAN markets like Cambodia, Laos, and Brunei because I haven’t studied them enough and because these countries are not on the radar yet for many entrepreneurs and venture capitalists due to population size.

Telehealth Bear Case in Emerging Southeast Asia?

Now with a somewhat clearer definition of “Southeast Asia” as a market, let’s dive into our arguments for a telehealth bear case emerging in Southeast Asia (in no specific order):

1. There’s no offline analogy for telehealth

Before the widespread adoption of messaging apps and video-conferencing platforms, doctors were already using the phone and email to practice ‘telehealth’ to reduce unnecessary follow-up visits, especially for chronic diseases.

In emerging Southeast Asian countries, there’s no hyper-local distribution of physician offices like in the US or Europe where GPs can develop a personal and ongoing relationship with regular patients. It is in this particular setting that we saw the initial applications of telehealth aimed at reducing the cost and inconvenience of an office visit or a home visit, often after the initial visit.

Looking at the unique nature of the healthcare supply chain in emerging SEA, this close family physician-patient relationship was never there. Thais, Indonesians, and Burmese are used to going straight to major hospitals and consuming healthcare in a more transactional versus relational nature. Lacking this family physician reference point, it is much more difficult for patients in emerging SEA to grasp the full value of telehealth. This has led to few people willing to pay for telehealth services, with many often preferring to spend the money on traveling to hospitals to see a doctor in person.

2. There are not enough good doctors to go around

The typical bull case argument for telehealth in emerging SEA is that it enables healthcare access for people living in remote areas. This argument relies heavily on the assumption that there’s enough supply of doctors to go around.

However, with only 0.4 and 0.8 doctors per 1,000 people in Indonesia and Thailand, respectively (versus 2.6 and 2.3 per 1,000 people in the US and Singapore, respectively), it’s clear the biggest bottleneck in the healthcare value chain in emerging SEA countries is the lack of doctors, period.

(This is a similar issue faced by many career and job marketplace platforms in Southeast Asia. In a market where demand far outweighs supply, many of these HR startups have had to resort to traditional recruitment models chasing talent while still masquerading as self-serve, scalable platforms.)

As a result, many experienced doctors have no lack of offline demand and unsurprisingly opt to practice at more prestigious hospitals. This leaves postgraduate/medical residency doctors to be most active on telehealth platforms, and are often part-time and underpaid. Like drivers for Grab and Gojek, these doctors often contract for multiple telehealth platforms and steer towards the ones with the greatest payout. With more telehealth players entering the space, prices get competed down and negatively impact unit economics.

3. Telehealth technology offers no moats

Not only has telehealth been around for ages, today’s telehealth applications can be easily developed using open source software like WebRTC or using commercially available messaging APIs like SendBird, MessageBird, and Qismo.

Since telehealth technology in and of itself doesn’t offer any moats, startups need to secure exclusive and/or quality supply, which is hard to find unless you happen to own a hospital or have so much demand it can make up for the financial and social capital doctors are currently getting through offline work.

To seize the COVID tailwind, hospitals are also jumping into telehealth using the likes of Zoom to go direct-to-consumer with its top doctors and bypassing third-party telehealth platforms.

Telehealth technology has become a commodity:

“There are some strictly “pipes” companies — like VSee, SecureVideo, Klara, Trillian, Spruce, and others — that simply provide a HIPAA compliant video conference solution, with the opportunity to customize to your electronic health record (EHR). These are commodities. It’s tough to make money here because the product simply increases the privacy/security of a basic video chat platform, and the entire potential user-base is the 1.5m doctors, NPs, and PAs in the US (compared to Zoom and Microsoft Teams/Skype with greater than 100m and 85m daily active users, respectively).” – Healthy Ventures

4. Humans are creatures of habit and will soon return to their ‘Old Normal’

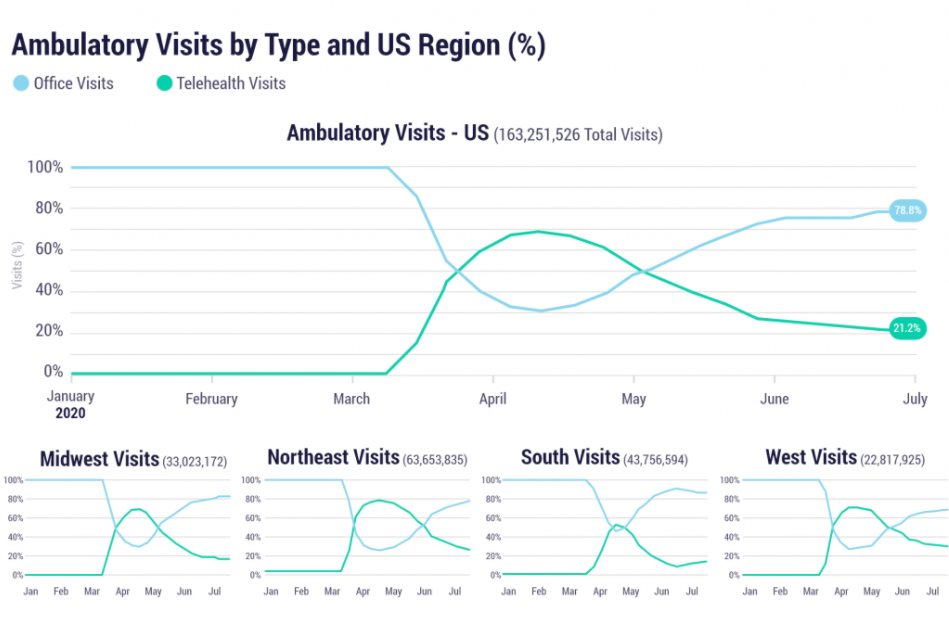

Remember when we were all locked up at home in March and April during peak COVID? When every pundit was proclaiming ‘New Normal’ and a world forever changed? Well, recent US EHR data shows the percentage of telehealth visits is down to 20 percent from the peak of 77 percent in April. Humans are creatures of habit and even in the ‘New Normal’, still prefer to see a doctor in person.

5. Telehealth success in mature markets is proof of B2B adoption, not B2C

Teladoc (NYSE: TDOC) stock is up 177 percent since the beginning of this year. However, its financial success is not a testament to the success of telehealth as a concept. With a lackluster 5 percent utilization rate (i.e. 5 percent of employees using telehealth after HR departments paid 100 percent), Teladoc’s rise is stronger proof of the strength of its B2B sales team than B2C product-market fit.

“You can only be a commodity service for so long. At a certain point, you have enough members that the line item is large enough that you start to wonder what you’re paying for, and only 5% of people using it doesn’t look great. That’s why Teladoc’s blend of new deals started seeing more and more focus on paying on “visit-fee only” aka pay-per-visit, instead of per-member-per-month even if no one uses it.” — Nikhil Krishnan, Founder of ‘Out-of-Pocket’, previously Senior Industry Analyst at CB Insights

In a way, telehealth in mature markets is sold the same way enterprise IT software companies sell their applications to Fortune 500 CIOs and CTOs — through wining and dining.

Even in mature markets, where one would expect telehealth adoption to increase exponentially given COVID, users aren’t warming up that much to telehealth. This doesn’t bode well for pure-play telehealth startups in emerging SEA where market and user variables are less favorable.

Beyond Telehealth: Digital Health in Southeast Asia

One only needs to look at markets like China and India that share similarities with emerging Southeast Asian countries (+/- 5-10 years) to understand what may happen here. In China 15 years ago, I had to wake up at 5 AM to go to a hospital to get a ticket and wait several hours before seeing a doctor. This isn’t much different from what people in emerging Southeast Asian countries have to go through today, especially at public hospitals.

One of China’s largest healthcare platforms Ping An Good Doctor gets only 17 percent of its revenues from telehealth services after five years of operating. And even the 17 percent deserves a bit of nuance — 97 percent of the 17 percent came from Ping An, with Ping An Good Doctor charging fixed fees to Ping An Group companies for telehealth regardless of actual end user utilization (note how this isn’t very different from how Teladoc gets its ‘telehealth’ revenues). These numbers were last reported in 2017 and Ping An Good Doctor stopped disclosing them ever since.

Spring Rain Doctor, another major telehealth player in the Chinese market, lost 90 percent of its telehealth volume after pulling the plug on subsidies and charging more money.

DXY, another Chinese digital health platform, stated only two questions made up over half of its telemedicine appointments during COVID: “which symptoms indicate COVID-19, and how to wear a mask properly.”

The Indian market hasn’t been kinder to telehealth startups either. According to The Ken, “Lybrate’s business model of a marketplace for doctors has failed as patients are unwilling to pay for consults”.

In the same report, Prashant Tandon, CEO and co-founder of 1mg, was quoted saying “even though [telehealth consultations] are theoretically always unit economics-positive, as patients pay doctors and the platform earns a commission, the lack of scale when it comes to paying users makes additional paid services a must.”

During COVID, I picked up the hobby of investing in public equities. Whilst a rollercoaster ride, I noticed how similar it is to how entrepreneurs decide on a strategy and which products to build.

Howard Marks, the co-founder and co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, the largest investor in distressed securities worldwide, puts it this way in his famous 2006 memo to Oaktree clients:

“You can’t take the same actions as everyone else and expect to outperform.”

While many have gone to popularize Marks’ ideas and wisdom, most notably Peter Thiel in his book ‘Zero to One’ as well as the broader contrarian movement, nothing beats the simplicity of Marks’ 2-by-2 matrix as illustrated below.

“If your behavior and that of your managers is conventional, you’re likely to get conventional results — either good or bad. Only if your behavior is unconventional is your performance likely to be unconventional… and only if the judgements are superior is your performance likely to be above average. [emphasis in original]” – Howard Marks

Telehealth is the easy, consensus view, unfortunately, held by too many people, pundits, venture capitalists, incumbents, journalists, etc.

The secret to success in digital health in Southeast Asia is to take a harder, non-consensus view. But that alone is not enough; you need to continue to believe you’re right despite peer pressure and smart people telling you otherwise. As Marks puts it:

“Non-consensus ideas have to be lonely. By definition, non-consensus ideas that are popular, widely held or intuitively obvious are an oxymoron. [emphasis in original] Thus such ideas are uncomfortable; non-conformists don’t enjoy the warmth that comes with being at the center of the herd.”

Reach out if you’re interested in learning more about some of the non-consensus (and hopefully right) ideas we’re working on to improve healthcare in emerging Southeast Asia.

Plug and Play is a global innovation platform. Headquartered in Silicon Valley, we have built accelerator programs, corporate innovation services, and an in-house VC to make technological advancement progress faster than ever before. Since inception in 2006, our programs have expanded worldwide to include a presence in over 30 locations globally, giving startups the necessary resources to succeed in Silicon Valley and beyond. With over 30,000 startups and 400 official corporate partners, we have created the ultimate startup ecosystem in many industries. Companies in our community have raised over $9 billion in funding, with successful portfolio exits including Danger, Dropbox, Lending Club, and PayPal.

TechNode Global publishes contributions relevant to entrepreneurship and innovation. You may submit your own original or published contributions subject to editorial discretion.

Featured image credit: Unsplash