TechNode Global’s series on the Philippines will delve into why Filipino entrepreneurs and founders are attracting venture capital (VC) money in droves. In this second part, we explore the rise in Series B (and now, C) fundraising rounds out of the Philippines in 2021, and what it signals for the startup ecosystem as a whole. Seven founders share how much the Philippine venture ecosystem has changed and what needs to be done to keep it growing. Catch up with Part 1 here.

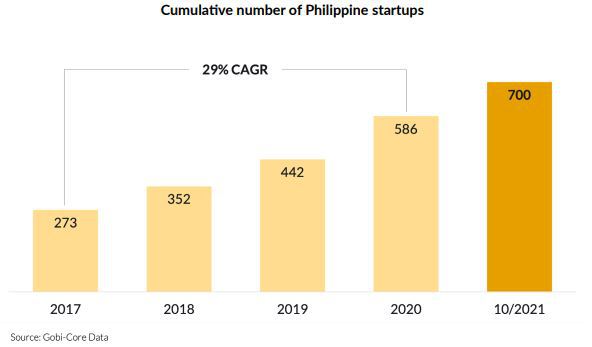

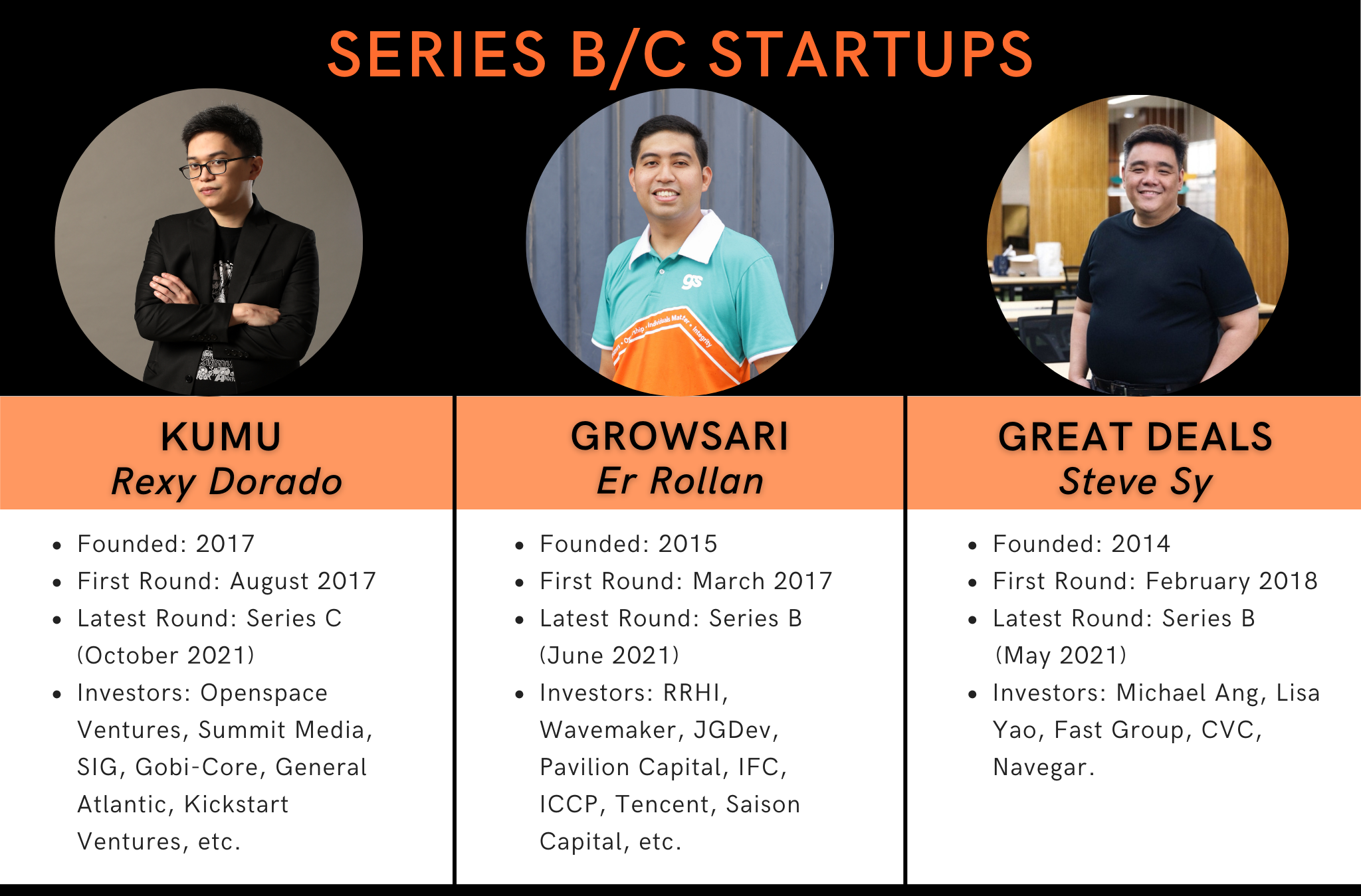

This year has been a banner one for the Philippine venture ecosystem, at least on the fundraising side. Not only did the country see its first Series B in May with e-commerce startup Great Deals raising $30 million, but it was also followed swiftly by two other Series Bs in June by live streaming app Kumu and B2B e-commerce platform GrowSari.

So 2021 was all set up to be the ‘Year of the Series B’ — a pretty serviceable headline all on its own, for a country that historically has not seen rounds beyond Series A and whose largest exit previously was in the sub-$100 million range — until October 27, when Kumu claimed the mantle of the Philippines’ first Series C.

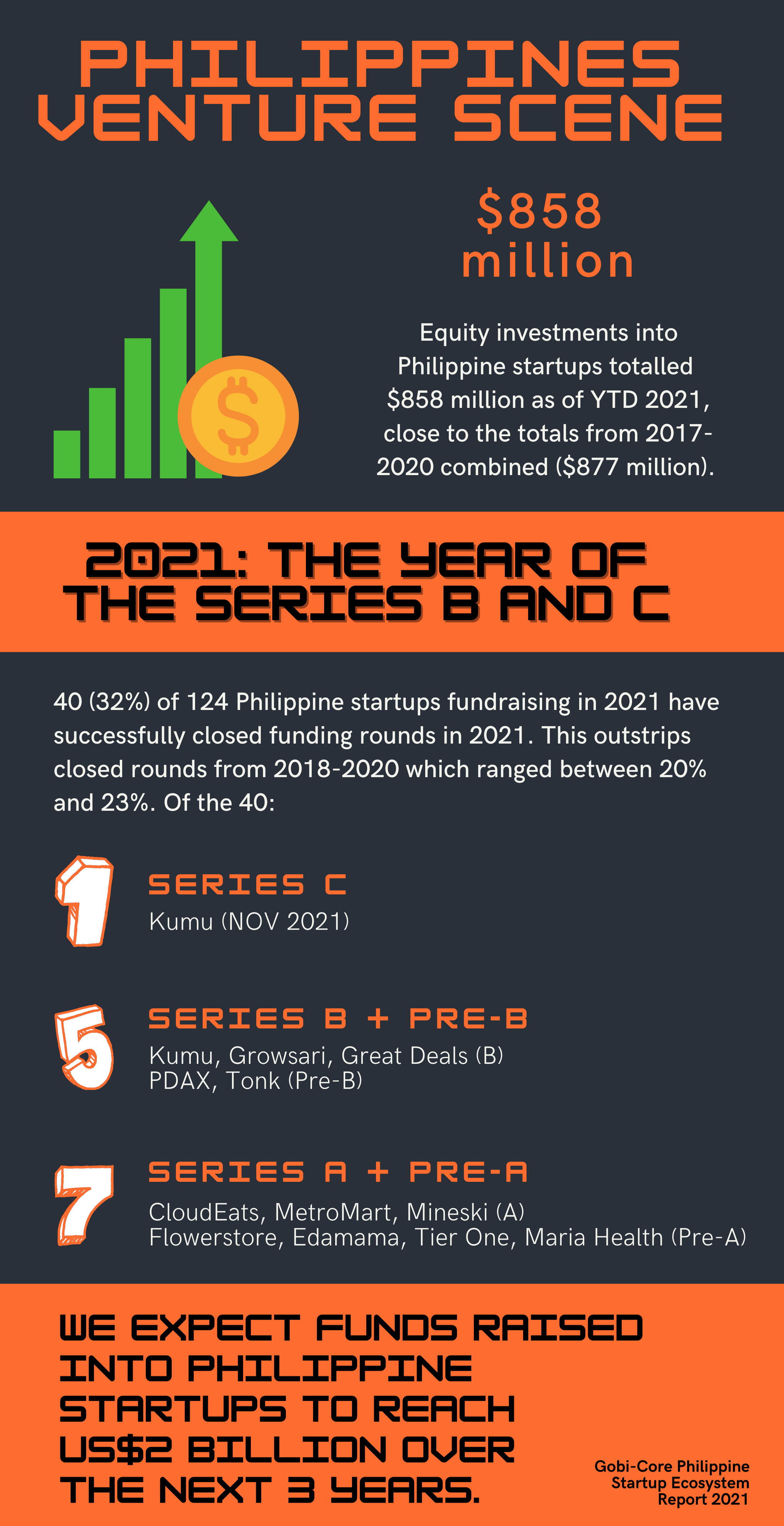

Admittedly, much of the exponential growth the local VC space has seen has been a result of the accelerated digitalization brought on by COVID-19 and its attendant work-from-home norms. A recent report by the Gobi-Core Philippine Fund found that Philippine startups have closed 40 rounds thus far this year for a total of $858 million, putting it on par with total funds raised over the previous three years (2018-2020: $877 million).

Not too shabby. Needless to say, given the wide variety of sectors, types of startups, and types of founders that have successfully fundraised, there is no one answer to why the venture ecosystem is booming now. As the race to be the Philippines’ first startup unicorn heats up (Mynt, a corporate fintech co-owned by Globe Telecom and Ant Financial, has laid claim to being the first unicorn), TechNode Global decided to get it straight from the horses’ mouths.

We spoke to founders behind three of the Series B startups (Kumu’s Rexy Dorado, GrowSari’s ER Rollan, and Great Deals’ Steve Sy), two founders of two Pre-B startups (PDAX’ Nichel Gaba and Tonik’s Greg Krasnov), as well as two other founders who have fundraised this year (Maria Health’s Vincent Lau and a founder who wishes to remain unnamed).

More founders, more VCs

Historically, both fundraising totals and exit proceeds faced price pressures in the Philippines as typically, acquirers would be corporate VCs (CVCs) or private equity (PE) firms affiliated with one of the Philippine family-owned conglomerates. Exits happened early, perhaps too early for regional or foreign VCs with bigger risk appetites and growth aspirations.

But pre-2021, foreign investors were few and far between, while independent VCs lacked the bargaining power and dry powder to bring early-stage startups into the growth limelight. A prime example would be Coins.ph, a fintech company co-founded by two foreign founders that was quickly bought by Gojek in January 2019 for $72 million, after raising two Series A rounds of $5 million each in 2016 and 2017. Clearly, it was a buyer’s market.

The founder who preferred to remain unnamed said: “Even though there are local VCs here, they don’t really behave like VCs because they’re part of corporate arms that tend to focus on ventures that have synergistic value and could be potential acquisition targets.

“Now, that’s changing because the startup ecosystem in the Philippines is a lot more vibrant. It wasn’t the case three or four years ago, when there were very few startups. Now there’s a lot more startups, which means you also have a lot more potential startup founders,” he added.

There are an estimated 700 startups in the Philippines as of October, a continuation of the trend seen from 2017 to 2020, when new startups mushroomed at a 29% compound annual growth rate.

“Because more people are seeking outside capital, local conglomerates have had to dissociate their venture arms so that they can more effectively take part in these opportunities,” the unnamed founder said.

The increased diversity in both founder and investor types have made the venture ecosystem more vibrant, driving valuations up and resulting in local VCs structuring independent investment committees to compete.

2021 has also marked many first-time investments in the Philippines by foreign VCs, particularly in larger rounds in line with their larger appetites. Kumu’ Series C, which pushed its total funds raised to $100 million, was American growth equity investor General Atlantic’s first Filipino bet.

Other first-time backers made plays in sectors they were familiar with, such as Hong Kong digital asset firm BC Group participating in cryptocurrency exchange PDAX’s $12.5 million pre-B round in August, or Warner Music’s backing of esports firm Tier One in April.

Leveraging foreign networks, diaspora

Nichel Gaba, Co-Founder of PDAX, said one reason the fintech company tapped foreign VCs from the outset was the minimum capital requirements required for crypto businesses and the lack of local VC appetite for funding a large amount.

“At the same time, a lot of the founders and VCs I had spoken with had either studied in the U.S. or worked outside the Philippines. I had my own network with potential investors that I could reach out to,” added Gaba, who was born in the U.S., grew up in the Philippines, and worked in the Hong Kong banking industry before returning to the Philippines to set up PDAX in 2017.

Foreign networks were also cited by Kumu co-founder Rexy Dorado, who was born and grew up in the Philippines before moving to the U.S. There, he met co-founder Roland Ros, a second-generation Filipino American. Together with a few other co-founders Ros and Dorado established Kumu in 2017.

“What helped more concretely in the early stage was our first ‘family and friends’ round was mostly Roland’s friends and family, and contacts in the U.S. They were a lot more used to investing in early-stage bets at a healthy valuation. At the time, our valuation was probably higher than what he would have been able to raise in the Philippines.

“We were able to get enough money at friendly terms because of that network we had built in the U.S. It would have been harder if we had started with a local raise, we would have started with a much lower valuation and (seen) much more intense terms at the beginning. In a way, that might have not set us up for success in the years after,” Dorado said.

GrowSari co-founder ER Rollan has a background similar to PDAX’s Gaba: after growing up and studying in the Philippines, he worked with FMCG giants as well as BCG in Singapore for several years before returning in 2016 to set up GrowSari with three non-Filipino co-founders he had met at various stops.

Rollan recounted, “B2B was just starting, and Wavemaker was one of the proponents of having a strong B2B portfolio. The biggest challenge, fundraising-wise, was that the Philippines was not considered a tech hotspot. Because we’re a Philippine-based company, there was a lot of skepticism around valuation.

“For the same sort of traction, Philippine startups saw a valuation discount. At the time, investors were benchmarking our valuation to other more common funding structures in the country, which were debt or convertible notes,” he added.

Rollan and his co-founders’ experience in BCG helped build an initial network, but VC pitching was a completely different ballgame from the corporate side they were used to.

“Going into a VC meeting, wearing a suit was probably not a good way to start. People want to see that you want to get your hands dirty and understand what’s happening on the ground. Frankly, it was a bit of a mindset change for us,” he said.

Four years later, GrowSari’s Series B of over $30 million involved a wide variety of investors, including Tencent and two Gokongwei-family-linked investors (Robinsons Retail Holdings Inc. and JG Digital Equity Ventures). Due to GrowSari’s inclusion story — digitizing sari-sari or mom-and-pop-stores — it also drew International Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World Bank Group.

Leveraging foreign networks is nothing new to Ukrainian serial entrepreneur Greg Krasnov. The founder of Tonik, the Philippines’ first neobank, is based out of Singapore and has founded a bank in Ukraine and multiple Asian FinTechs.

In May, Tonik announced a $17 million pre-B round led by Singapore’s iGlobe Partners and involving global investment firm Citius and Moscow-based Baring Vostok Private Equity.

But this is Krasnov’s second go at the Philippine startup scene, and the first time around, fundraising was much harder.

“I was a co-founder of Pera247, one of the first digital lenders in the Philippines. We knocked on a lot of investors’ doors three to four years ago, but it was very hard to get investor attention about the Philippines. We ended up selling it to another fintech company called AsiaKredit, because we just couldn’t succeed in fundraising. These days it’s much easier,” Krasnov said.

Getting on regional radars the creative way

Great Deals (founded 2014) and Maria Health (2016), took a less beaten path to getting institutional investors’ attention.

In May, e-commerce enabler GreatDeals raised a $30 million Series B led by logistics firm Fast Group (owned by the Chongbian family). Founder Steve Sy, however, had bootstrapped the business from 2014 until 2018.

“I started my business in 2014 as a sole proprietor, only setting up a corporation in 2017. By 2019, I had already had two angel investors and decided to join the StartCon pitching competition, which had AUD 1 million in prize money. We went to Australia for the final, representing the Philippines. There, I met my PE/VC advisor, and a year later I closed my Series A investor, PE firm Navegar,” Sy said.

Insurtech startup Maria Health recently closed a pre-Series A round led by InLife, the largest Filipino life insurance company. Maria Health founder Vincent Lau is an American expat who took a leap into the Philippines’ InsurTech space in 2015, armed with one strong Filipino connection: Paul Rivera, the founder of human resource startup Kalibrr.

Lau recounted, “I was born and raised in the Bay Area so Silicon Valley was my backyard. I actually have no connection to the Philippines. After a decade working in growth-stage startups, I wanted to solve a real problem and build something for the 99%. In the Philippines, there’s a huge under-insurance gap: of over 100 million people, only 2% have health insurance. That’s what drew me to the Philippines.”

Fast-forward to 2017, and Maria Health had an ecosystem in place and onboarded major HMOs (health maintenance organizations) and the insurers, but was facing a cash crunch.

“Fundraising was very difficult as we were still at a very early stage. If we weren’t able to raise a round, we would have to consider closing the business. I had this crazy idea to join The Final Pitch (a Shark Tank-like business reality show) where all the investors were Filipino, so they could relate to the health insurance gap we were addressing.

“We got funding from the Final Pitch of about $500,000. Through the show, we also picked up our first institutional investor, Wavemaker Partners. A year later, we raised another seed round through Gobi-Core. In terms of fundraising, we’ve found success in identifying the right investors who truly understand localized problems and opportunities. It’s not about talking to as many investors as possible, but finding the right investors,” Lau said.

Though headquartered in Singapore, Wavemaker is led by a Filipino, Paul Santos. Gobi-Core, meanwhile, is a joint venture between Core Capital (founded by three Cebu-based entrepreneurs) and pan-Asian VC Gobi Partners.

“The bare minimum of knowing that somebody can be trusted and isn’t a predatory investor is worth far more in the Philippine context than in more mature markets.” – Rexy Dorado, Co-Founder of Kumu

Finding the ‘good’ angels

A common refrain by all founders was the importance of getting off on the right foot: starting with a trustworthy and fair angel investor.

Kumu founder Rexy Dorado said, “We lucked out in that we worked with Lisa (Gokongwei-Cheng) and Summit Media in 2018. She’s known now — maybe not publicly, but within the startup space — as one of the best angel investors to work with. She’ll give you fair terms.

“The bare minimum of knowing that somebody can be trusted and isn’t a predatory investor is worth far more in the Philippine context than in more mature markets. Lisa was our first major local investor, and through Summit Media as our first institutional investor,” he remarked.

In 2018, this was a rarity among local players, who were typically more conservative yet aggressive. Investors were taking majority stakes for small amounts of funding, or putting in draconian clauses.

“I’ve talked to a founder who took some institutional money, and one of the terms was that if his startup went under, the investor would absorb all the intellectual property. Things like that were tolerated back then because there were just fewer alternatives.

“At the regional and international level, we still needed to educate investors. The largest exit of a true startup was in the sub-$100 million range, which gave foreign investors a mental ceiling of what a home run means in the Philippines,” Dorado added.

Steve Sy of Great Deals was not actively fundraising when he secured his two angel investors: Tiger Machinery president Michael Ang and Richprime Global managing director Liza Yao-Bate.

Sy recounted, “In late 2017, P&G came knocking on my door, asking if Great Deals could take their business. But just to be able to do that, I needed around $800,000 of working capital to expand my warehousing capabilities, hire people and buy products. That was my crossroads moment. After much thought, I decided to get an investor. So I shared a simple Excel and pitch deck with Michael, who was a friend of mine. He invested $400,000 in February 2018.

“In 2019, Richprime Global — one of the largest toy distributors in the Philippines — was a client. I had lunch with Liza, expecting to talk about how to grow her business online. She asked me if I was open to investment, and I said yes and that was done,” he said.

Solving the talent problem

A key part of growing beyond the early stage is having skilled, trustworthy tech talents to build growth stage products and services. Several founders brought up the need to nurture and attract Filipino tech talents, a recurring theme given the country’s dependence on remittances and the large population of overseas Filipino workers.

PDAX founder Nichel Gaba believes a big part of why the Philippines remains under-invested is that Filipinos are predisposed to be a global workforce, being fluent in English and having a strong affinity for Western culture.

“It’s no secret that almost 10% of our workforce are actually overseas. These are our most talented and most ambitious people. Automatically, they leave the country. Global servicing hubs in India and Malaysia are consuming a lot of our tech talents. Even the Filipinos who work in hubs in the Philippines are doing back-office work for Accenture or HP.

“Who can fault them, when the choice for fresh grads is between $1,000 a month (three times the minimum wage) to support their families, or joining a startup? That’s why funding is so important for startups. Now, we can compete for the best talents and make it a point to pay above average, very competitive wages,” Gaba remarked.

GrowSari’s ER Rollan concurs, noting that rising interest in working for startups is due to there being more founders, forums, and events about local startups. “When I started working, the bias was to work for an MNC. But now, there is a genuine talent fight that MNCs are having for fresh grads and top talent.

“While funding has definitely helped us get top talents, it’s also tricky. In the beginning, I could only pay so much so there was this assurance that people joining your company are there for the vision. As startups tend to get more money and improve their ability to pay, the challenge is for us to screen for fit and motivation,” Rollan remarked.

Greg Krasnov may be building a Philippine-focused neobank, but Tonik’s team is global, with four to five nationalities in its top team. Being a foreign founder, Krasnov chose to leverage his international networks to bridge the talent gap.

He said, “I’m probably an atypical founder in that regard. Singapore, where I live now, is my eighth country. It’s easier to source elements you’re missing when you have a global perspective.

“We built out our R&D Center in India instead of the Philippines because there is extremely limited know-how in digital banking. We have 150 people in Chennai, and that just wouldn’t have been possible in Manila. Meanwhile, our head of UX and a few of our UX people are based in Europe, and we’ve set up a mini-hub for UX in Kiev,” Krasnov noted.

Kumu’s Dorado points out that there remains a need for talents who have been through the process of scaling a startup, and then go on to become founders of the next wave of startups.

“We’ve had a lot of help from team members like Crystal Widjaja, who was at Gojek four years ago during its hyper-growth mode. She helped us reorganize our product team in six months. This could have taken us many years to get right. That kind of talent has been a bit harder to come by for the Philippines until recently.

“I think it’s going to change when the Gojek and Grab IPOs happen. That’s going to untether a lot of great talents who are going to be looking for their next step, and Filipino founders can take advantage of that,” he noted.

A community-based ecosystem

Kumu’s Dorado and Roland Ros are also co-founders of Sinigang Valley, a Philippine version of Silicon Valley located in Makati City.

Dorado explained, “Our goal is to get everybody spending more time in the same place, colliding a bit more, because there are things you can’t really learn from textbooks or the Internet. You just have to have other entrepreneurs that you can trust and get insights from, who to trust to work with or take investments from. What does this investor/partner care about and how do I frame my venture so that it comes off as relevant to them? What is the market and what isn’t?

“In terms of valuation and control rights, you’re not going to find that (information) anywhere publicly. Founders can pick each other’s brains in terms of day-to-day problem solving like hiring for a specific role, ironing out teams, or understanding regulatory compliance processes.

“What’s the right way to give stock options to my team? All of those things– you can’t find them from a Google search but you can ask anyone who’s been working on building a venture for several years in the Philippines and they’ll give you something helpful to work off of,” he said.

“(Conglomerates) are comfortable not being in control, and letting entrepreneurs drive. That’s the beauty of it right now.” – Steve Sy, Founder of Great Deals

Only getting hotter

Given the ‘sticky’ nature of new digital service users, many founders believe that both funding and user base will grow.

“What usually prevents people from trying digital is the fear of the unknown. In e-commerce purchases, insurance, and many other sectors, there was a big step up during COVID. But even in the countries where COVID has pretty much gone away now, that trend stayed.

“Once people tried e-commerce, they loved it and stuck with it. They stopped going to malls and supermarkets because it saves them time. Same thing with financial services. This was a one-time boost to the whole sector. I think it will only accelerate from here,” Tonik’s Krasnov said.

Maria Health’s Lau concurred, noting that the startup has seen a 200% increase in the demand for health insurance. “Post-pandemic, this won’t be a flash in the pan because it’s accelerated education and awareness of the importance of health insurance.

“Covid has flipped the world 180 degrees. What you’re now seeing is a much bigger interest in the Philippines and a consensus that technology can transform traditional industries and that the Philippines is ripe for innovation and disruption,” he said.

Meanwhile, Great Deals’ Steve Sy believes there’s much more room to grow as e-commerce sales account for less than 3 percent of total retail sales.

“People are adopting these new technologies left and right, so it’s a good bet on the future. Traditional billionaires are now open to investing in startups because they know that there will be a lot of other investors coming in once the business grows to a certain size.

“Before, most of the conglomerates in the Philippines were looking for acquisitions. Now, they’re open to investments and minority shares. They are comfortable not being in control and letting entrepreneurs drive. That’s the beauty of it right now,” Sy enthused.

In Part 3 of this series, TechNode Global will explore how much COVID-accelerated digitization was a boon for startups in the so-called ‘Iron Triangle’, comprising e-commerce, logistics, and fintech startups, and what sectors are set to take off in the second wave.